Quantitative Easing Or Not? A Primer On The Fed’s Shiny New Tool

The debate around whether or not the Bank Term Funding Program is a form of quantitative easing overlooks the most important point: Liquidity is the name of the game for global financial markets.

Relevant Past Articles:

Quantitative Easing Or Not?

The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) is a facility introduced by the Federal Reserve to provide banks a stable source of funding during times of economic stress. The BTFP allows banks to borrow money from the Fed at a predetermined interest rate with the goal of ensuring that banks can continue to lend money to households and businesses. In particular, the BTFP allows qualified lenders to pledge Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities to the Fed at par, which allows banks to avoid realizing current unrealized losses on their bond portfolios, despite the historic rise in interest rates over the past 18 months. Ultimately, this helps support economic growth and protects banks in the process.

The cause for the tremendous amount of unrealized losses in the banking sector, particularly for regional banks, is due to the historic spike in deposits that came as a result of the COVID-induced stimulus, just as bond yields were at historic lows.

Shown below is the year-over-year change in small, domestically chartered commercial banks (blue), and the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield (red).

TLDR: Historic relative spike in deposits with short-term interest rates at 0% and long-duration interest rates near their generational lows.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The reason that these unrealized losses on the bank’s security portfolios have not been widely discussed earlier is due to the opaque accounting practices in the industry that allow unrealized losses to be essentially hidden, unless the banks needed to raise cash.

Shown below is the year-over-year change in cash assets of small, domestically chartered commercial banks.

The BTFP enables banks to continue to hold these assets to maturity (at least temporarily), and allow for these institutions to borrow from the Federal Reserve with the use of their currently underwater bonds as collateral.

The impacts of this facility — plus the recent spike of borrowing at the Fed’s discount window — has brought about a hotly debated topic in financial circles: Is the latest Fed intervention another form of Quantitative Easing? Is all balance sheet expansion created equal?

In the most simple terms, quantitative easing (QE) is an asset swap, where the central bank purchases a security from the banking system and in return, the bank gets new bank reserves on their balance sheet. The intended effect is to inject new liquidity into the financial system while supporting asset prices by lowering yields. In short, QE is a monetary policy tool where a central bank purchases a fixed amount of bonds at any price.

A similar policy tool that can be viewed as an even more heavy-handed approach is yield curve control (YCC), where the central bank focuses on targeting specific interest rates along the yield curve of the government bond market. While similar to QE, YCC control can be thought of as a monetary policy tool where the central bank purchases a potentially unlimited amount of bonds to keep the market at a fixed price.

Now, let’s examine the Bank Term Funding Program.

The rest of this article is open to paying members only. Here’s what’s behind the paywall 🔏:

Comparisons between BTFP and yield curve control. 🚨

Looking back to the Fed intervention in the overnight repo market in 2019. 🌊

The way out of 120% debt-to-GDP… 🚧

Is BTFP An Example Of YCC?

Source: Bloomberg

Though the Fed has attempted to communicate that these new policies are not balance sheet expansion in the traditional sense, many market participants have come to question the validity of such a claim.

If we simply look at the response from various asset classes since the introduction of this liquidity provision and the new central bank credit facility, we get quite an interesting picture: Treasury bonds and equities have caught a bid, the dollar has weakened and bitcoin has soared.

In the week following the BTFP announcement, JPMorgan Chase stated that it expected BTFP usage to be substantial, with the maximum uptake of the facility to be up to $2 trillion. While $2 trillion of usage of the facility is likely a bit hyperbolic — $2 trillion is the total par amount of bonds held by U.S. banks outside of the largest five institutions — let’s reduce the noise and analyze the BTFP facility.

On the surface, the facility is purely to “provide liquidity” to financial institutions with constrained balance sheets (read: mark-to-market insolvency), but the real implications should be viewed with Occam’s razor.

Occam’s Razor: A principle in philosophy and problem-solving that states that simpler explanations or hypotheses should be preferred over more complex ones when faced with competing explanations for a given phenomenon. In other words, when two or more explanations are equally valid, the one that requires the least number of assumptions is more likely to be correct.

If we closely examine the effect of BTFP from first principles, it is clear that the facility provides liquidity to institutions experiencing balance sheet constraint, while simultaneously keeping these institutions from liquidating long-duration treasuries on the open market in a firesale.

To summarize, yield curve control is when a central bank increases its balance sheet to cap the yields on sovereign debt, while BTFP sees the Fed increase its balance sheet to cap U.S. Treasury yields that are held on bank balance sheets.

BTFP is “Not QE, QE.”

While the BTFP has only extended $64.4 billion worth of loans to the banking sector, this program has kept over $60 billion worth of long-duration securities from getting liquidated into the open market, which would have sent yields higher, while also having potential deflationary knock on effects due to bank insolvencies and/or halting of credit expansion. This comes at a time when the banking sector is experiencing a massive flight of deposits, as rates on savings and checking accounts are far below the risk-free rate available in money market funds and short-term Treasury securities.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

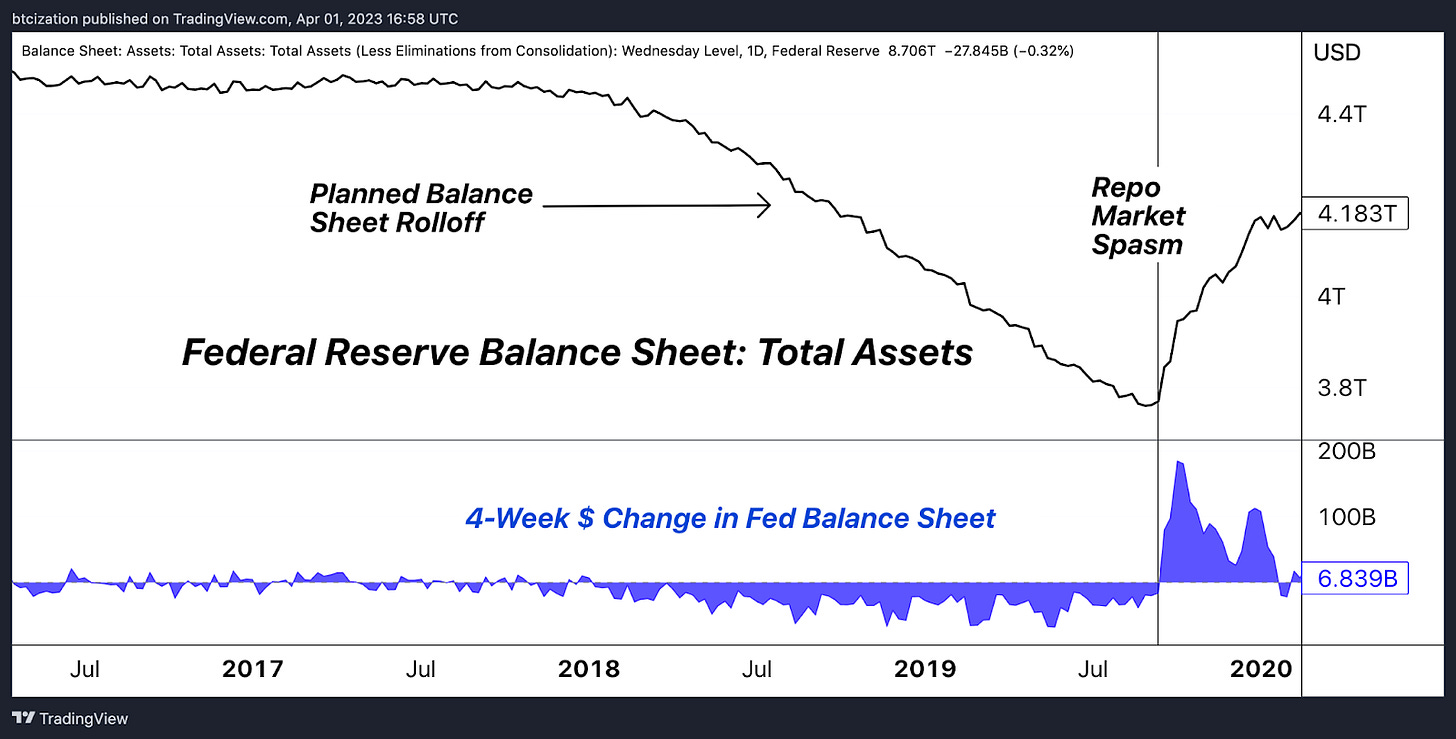

The situation that led to the BTFP is eerily reminiscent of the 2019 Fed intervention in the overnight repo market.

Source: Federal Reserve

The abbreviated version of the story: In September 2019, the U.S. repo market experienced a sudden and unexpected spike in overnight interest rates. The repo market is where banks, hedge funds, and other institutions go to lend and borrow short-term funds, with government securities serving as the typical form of collateral. The sudden overnight rate increase was due to a confluence of factors, including a large issuance of U.S. Treasury securities, corporations withdrawing cash from money market funds to make quarterly tax payments, and banks maintaining higher reserves due to regulatory requirements. The liquidity squeeze led to a sharp increase in repo rates, which in turn, put upward pressure on other short-term borrowing rates.

The Fed responded quickly to the situation by injecting liquidity into the repo market by conducting overnight and term-repurchase operations, which provided short-term cash loans to financial institutions in exchange for Treasury securities. The intervention aimed to bring the repo rate back in line with the federal funds rate — the Fed’s main policy rate.

In addition to the repo operations, the Fed also started purchasing Treasury bills to increase the level of bank reserves, which aimed to reduce the risk of similar liquidity shortages in the future. Although the Fed refused to call the process QE since it did not involve purchasing long-term bonds to lower long-term interest rates, the market reacted positively by sending the stock market to fresh all-time highs shortly thereafter. Volatility in markets eased as market participants celebrated the fresh tailwinds of a supportive Fed after a brief stint of balance sheet reduction.

Academics and economists can debate the nuances and intricacies of Fed policy action until they are blue in the face, but the reaction function from the market is more than clear: Balance sheet number go up = Buy risk assets. Whether that is the “correct take” or not from an academic standpoint is completely irrelevant…

Do you want to make money, or “be right”?

What To Watch For

The Fed has increased its balance sheet by $366 billion over the last month due to discount window lending and the BTFP, but the central bank is still insistent that it plans to undergo further reduction of its securities portfolio via its quantitative tightening programs.

Source: Nick Timiraos

Source: Nick Timiraos

With the rolloff of its securities portfolio along with the supportive introduction of the BTFP, the Fed can likely continue to wind down its securities portfolio for awhile before serious strain emerges in the real economy, which looks to be coming sometime in the second half of 2023, as a confluence of factors hit the U.S. market.

Of these factors, we see aggregate consumer savings dwindling, core inflation still running piping hot (reinforcing stubbornly high policy rates), the Treasury General Account (TGA) running low as U.S. debt ceiling negotiations are set to unfold and lastly, the lag effects on monetary policy are likely to fully set in by that point.

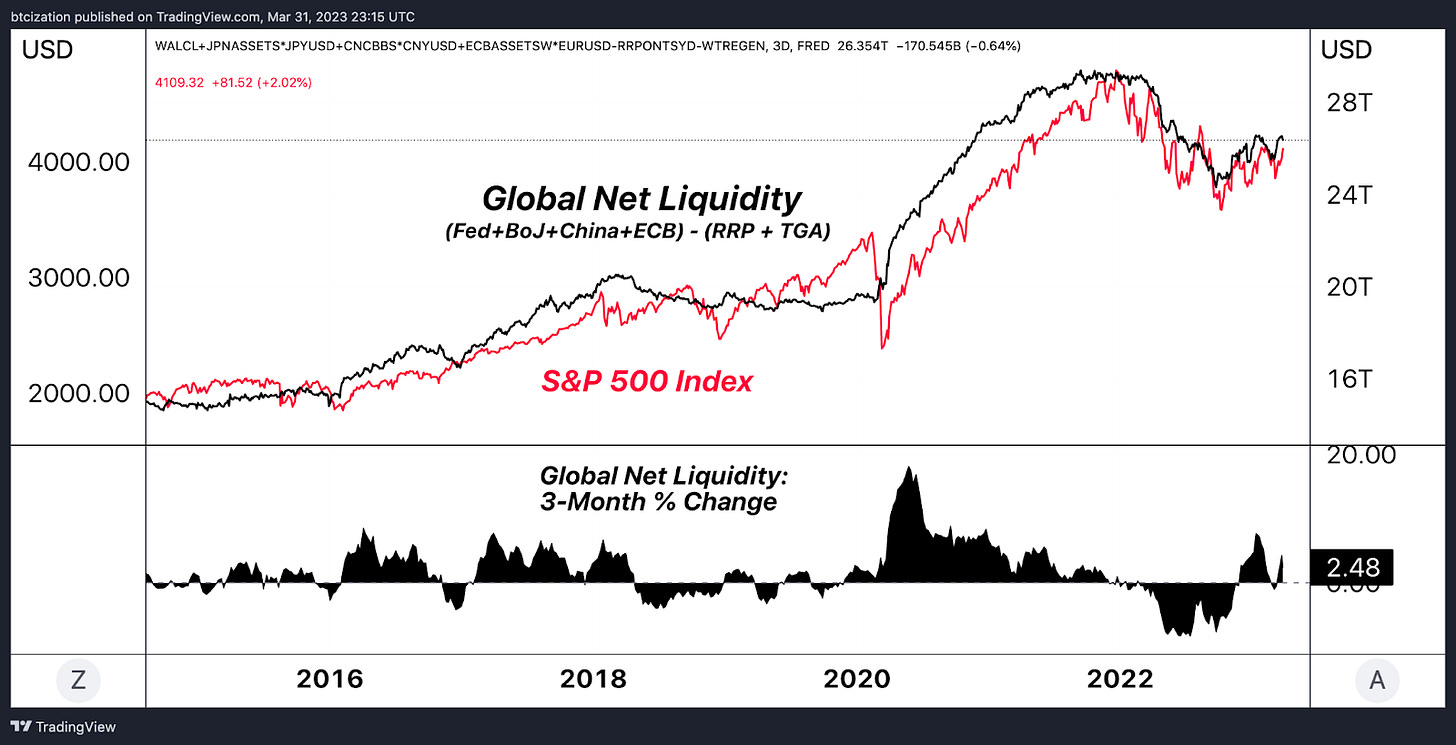

As highlighted before, market dynamics respond almost entirely to liquidity, and we should look not just at the Federal Reserve balance sheet, but rather at a multitude of dynamics in the U.S., as well as on a global scale.

When looking at our equation for Net Liquidity, which combines the Fed balance sheet and subtracts the balances in the TGA and reverse repo facility (as drawdowns in each of these facilities introduces liquidity back into financial markets), we can see that liquidity following the COVID-19 stimulus bazooka has been the dominant driver in financial markets.

Further investigation into the individual components of this equation can show that much of the Fed’s tightening has been offset by a drawdown in the TGA in recent months.

With the debt ceiling fast approaching and the TGA balance diminishing, it is overwhelmingly likely that Congress will eventually agree to raise the debt ceiling — as is tradition — which will be followed by the Treasury issuing hundreds of billions worth of debt securities into the market (read: going further into debt). This will be a massive drag on liquidity at the same time the Fed is attempting to reduce holdings in its security portfolio.

While the 1-year credit defaults swap to protect against the U.S. government default has soared past Great Financial Crisis highs, we assign approximately a 0% probability that the U.S. will be allowed to nominally default on its debt.

Source: Michael McDonough

Instead, the likely outcome is that an agreement to raise the debt ceiling is reached, and the U.S. issues debt securities into the open market, crowding out less creditworthy borrowers while doing so, raising the borrowing costs for every debtor — who is more creditworthy than a government with de facto access to a money printer?

This could provide some intense headwinds for markets in the second half of 2023, as stimulus-hungry markets will start to starve as their liquidity lifeline drip suddenly diminishes.

Make no mistake about it, the entire game is now about liquidity in global financial markets. It did not used to be this way, but central bank largesse has created a monstrosity that knows nothing other than fiscal and monetary support during times of even the slightest distress. While the short-to-medium term looks uncertain, market participants and sidelined onlookers should be well aware as to how this all ends.

Perpetual monetary expansion is an absolute certainty. The elaborate dance played by politicians and central bankers in the meantime is an attempt to make it look as if they can keep the ship afloat, but in reality, the global fiat monetary system is like an irreversibly damaged ship that’s already struck an iceberg.

Let us not forget that there is no way out of 120% debt-to-GDP as a sovereign without either a sustained period of inflation above the level of interest rates, or a massive unforeseen productivity boom. Given that the latter is extraordinarily unlikely to occur in real terms, financial repression, i.e., inflation above the level of interest rates, appears to be the path going forward.

Financial repression is one term for this; monetary debasement is another.

A solution exists, and it’s in the name of our publication.

Final Note

For the layman, there is no dire need to get caught up in the schematics of the debate whether recent Fed policy is quantitative easing or not. Instead, the question that deserves to be asked is what would have happened to the financial system if the Federal Reserve didn’t conjure up $360 billion worth of liquidity from thin air over the last month? Widespread bank runs? Collapsing financial institutions? Soaring bond yields that send global markets spiraling downwards? All were possible and even likely and this highlights the increasing fragility of the system.

Bitcoin offers an engineering solution to peacefully opt out of the politically corrupted construct colloquially known as fiat money. Volatility will persist, exchange rate fluctuations should be expected, but the end game is as clear as ever.

Thank you for reading Bitcoin Magazine Pro, we sincerely appreciate your support! Please consider leaving a like and letting us know your thoughts in the comments section. As well, sharing goes a long way toward helping us reach a wider audience!

Fire article. Keep it simple boys, stack sats. LOL @ the hobbit meme too.