The Deep Dive Monthly Report, February 2022 Preview

Become a premium subscriber to The Deep Dive to get access to this monthly report and all of The Deep Dive research. We will release the full monthly report to free subscribers next Monday, March 7.

Sign up with the button below to get a premium subscription 30-day free trial and access to the full report.

PREPARED BY:

Dylan LeClair, Head of Market Research

Sam Rule, Lead Analyst

Summary:

Macroeconomic Backdrop

Equity Market Correlation

Treasury Market Yields

Eurodollar Futures and Rate Hike Probability

Military Escalation in Ukraine

Trade Wars, Currency Wars and Kinetic War

The Exorbitant Privilege

Eroding Trust Between Sovereigns

A Bifurcating Global Monetary Order

Bitcoin: Risk-On or Risk-Off Asset?

Bitcoin as a Monetary Commodity

On-Chain Market Dynamics

Supply Held, Last Active Supply

Reserve Risk

Bitcoin Derivatives

Perpetual Swaps Market

Quarterly Futures

Concluding Thoughts

Long-Term View

Reserve Currency

Macroeconomic Backdrop

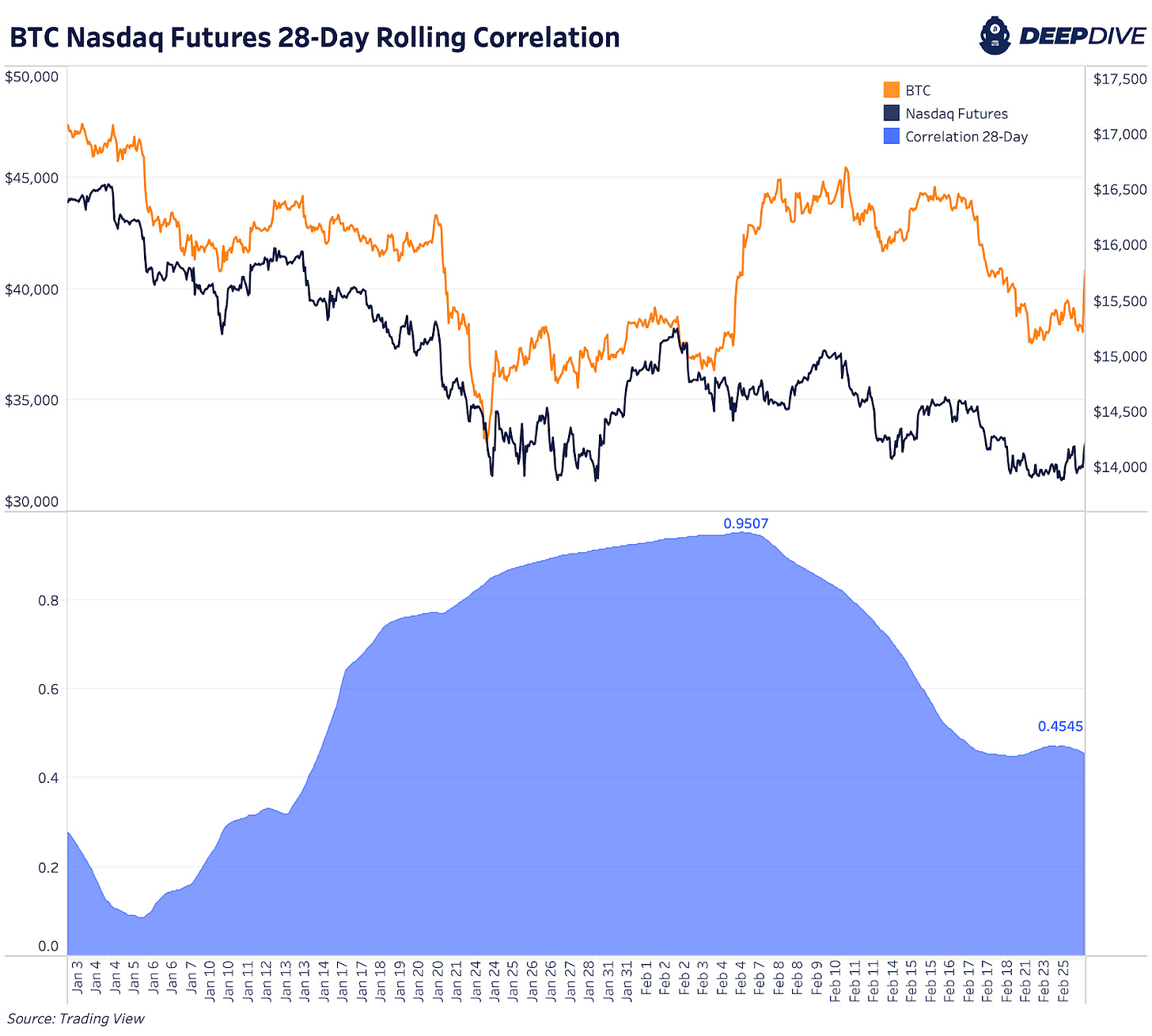

In our January 2022 Monthly Report, we covered bitcoin’s near 1:1 correlation with the Nasdaq over the previous four-week period, finishing the month with a correlation coefficient of 0.931. The relationship between the two asset classes reached a rolling four-week high of 0.95, before beginning to decouple as February progressed.

Bitcoin had been in a broad downtrend since November when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced the Fed’s policy shift toward taming inflation, due to the consumer price index hitting all-time highs. It wasn’t exactly the 40-year high in consumer price inflation that was the bearish catalyst for risk assets, but rather the reaction by the Federal Reserve Board and Chairman Powell that followed.

As the Fed merely signals that future hikes were in the cards, credit markets react swiftly and succinctly, with the short end of the treasury curve selling off leading to higher bond yields and flattening yield curve.

Eurodollar Futures, a futures market for the Fed Funds Rate, shows the steep advance in the market’s expectation for Fed rate hikes in 2022, leading into February, before sharply reversing course as markets teetered. The predicted Fed Funds rate for December 2022 reached as high as 2.11% on February 11 before the implicit Fed Put began to get priced into markets, with this figure now at 1.56% at the time of writing, nearly two full 25bp hikes.

The market now assigns the probability of two, full rate hikes in the upcoming March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting at 0%, with a 3.13% chance that the Fed doesn’t even hike at all.

Military Escalation In Ukraine

The purpose of this section is not to predict the outcome of the escalating conflicts between Russian and Ukraine, and more broadly the measures taken by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries against Russia as a result, but rather to probabilistically examine the potential scenarios and how one should look to position themselves financially. It also should be noted that this next section on geopolitical conflicts is not meant to serve as an in-depth history lesson, but rather to provide some context to the driving geopolitical forces impacting financial markets. While many analysts and financial market speculators are watching hour-by-hour updates of the escalation unfold, we prefer a wider view when assessing the current events.

A summarized form of the situation is as follows: Russia, the world’s third-largest oil producer and second-strongest military force invaded Kyiv, Ukraine, as Putin declared that Russia could not feel "safe” because of what he claimed was a constant threat from modern Ukraine due to the country’s increasing involvement with NATO.

Tensions between the two nations have been high since Ukraine declared itself independent of the Soviet Union in 1991 and moved to a market economy. In 2014, in what later became known as the Revolution of Dignity, the Ukrainian president and government was overthrown following a series of violent riots and protests, which led to the Russian invasion and Annexation of Crimea.

This is all to say that the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine is not something that developed seemingly overnight but that has been in the cards for decades. But why would Putin strike now, and what are the second order effects of the conflict?

It’s important to evaluate the specific battlefields in which this war is unfolding, of which the kinetic warfare occuring in Kyiv might be the least impactful.

Trade Wars, Currency Wars And Kinetic Wars

While all of the focus of the current military escalation occuring in Ukraine, the real war being fought by Putin is one of monetary and economic proportions. Over the last decade, Putin has made a deliberate decision to divest U.S. dollar holdings into alternatives like gold, the yuan and the euro. During the same period, he has verbally stated his disdain for the U.S. dollar and its role as the world reserve currency on multiple occasions.

In the summer of 2021, Putin said this of the dollar, “The US will regret using the dollar as a sanctions weapon … Russia's oil companies could stop using the currency which will harm the US dollar's global currency position.”

Putin also had this to say about the dollar and America’s exorbitant privilege as the issuer of the world reserve currency, “They are living beyond their means and shifting a part of the weight of their problems to the world economy.”

“They are living like parasites off the global economy and their monopoly of the dollar.”

What does Putin exactly mean when he is referring to the U.S. as “parasites off the global economy and their monopoly of the dollar”? What Putin is referring to is the United States’ twin deficit status, as a nation with both a current account deficit and a budget deficit.

A country with a current account deficit is an economy that imports more than it exports while also spending more than it generates in revenue (tax receipts). In theory, a country's trade balance and relative currency values work to find a natural equilibrium as countries that run a current account surplus (export more than it imports) find that their currency appreciates as money flows into their economy. Value is then stored in the strength and stability of the currency. But this dynamic decreases global competitiveness as labor and manufacturing seek to migrate to cheaper jurisdictions with weaker currencies, and hence lower production and labor costs.

Conversely, countries that run current account deficits in tandem with budget deficits will accrue debts to foreigners, leading to an increasing amount of foreign asset ownership and investment in the country. Ultimately, this leads to a far weaker currency, meaning diminished purchasing power in foreign markets but an increasing level of attractiveness in its labor and manufacturing markets.

This is, in theory, the self-correcting mechanism of trade balances and capital flows between nations, but the world doesn’t work based on theory.

Due to the Triffin dilemma, this self-correcting mechanism does not take place. The Triffin dilemma was a problem first identified by Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, who pointed out that the country with the global reserve currency must be willing to supply the world with an extra supply of its currency to fulfill world demand for foreign exchange reserves, leading to a trade deficit.

However, unlike other economies, due to the reserve status nature of the currency (meaning international demand outside of the domestic economy), the currency (in this case the U.S. dollar) remains relatively strong, translating to poor competitiveness in global labor and manufacturing markets.

The Exorbitant Privilege

This exorbitant privilege is a term for a country that holds reserve currency status, in which it doesn’t face a balance of payment crises due to its imports being denominated in its own currency. This position held by the U.S. seemingly enabled the U.S. to “print” its dollars in exchange for other countries' physical commodities, like oil, and this was a great deal for all parties while foreign nations could receive a real return on their dollars in the form of U.S. Treasuries.

However, it is our belief that we have reached the end of the 40-year bull market in bonds for numerous reasons, with an expectation that creditors (bond holders) are in for a sustained period of negative real returns going forward. Displayed below is the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury subtracted by the year-over-year change in the consumer price index.